- The Hominic

- Posts

- Have You Met Art?

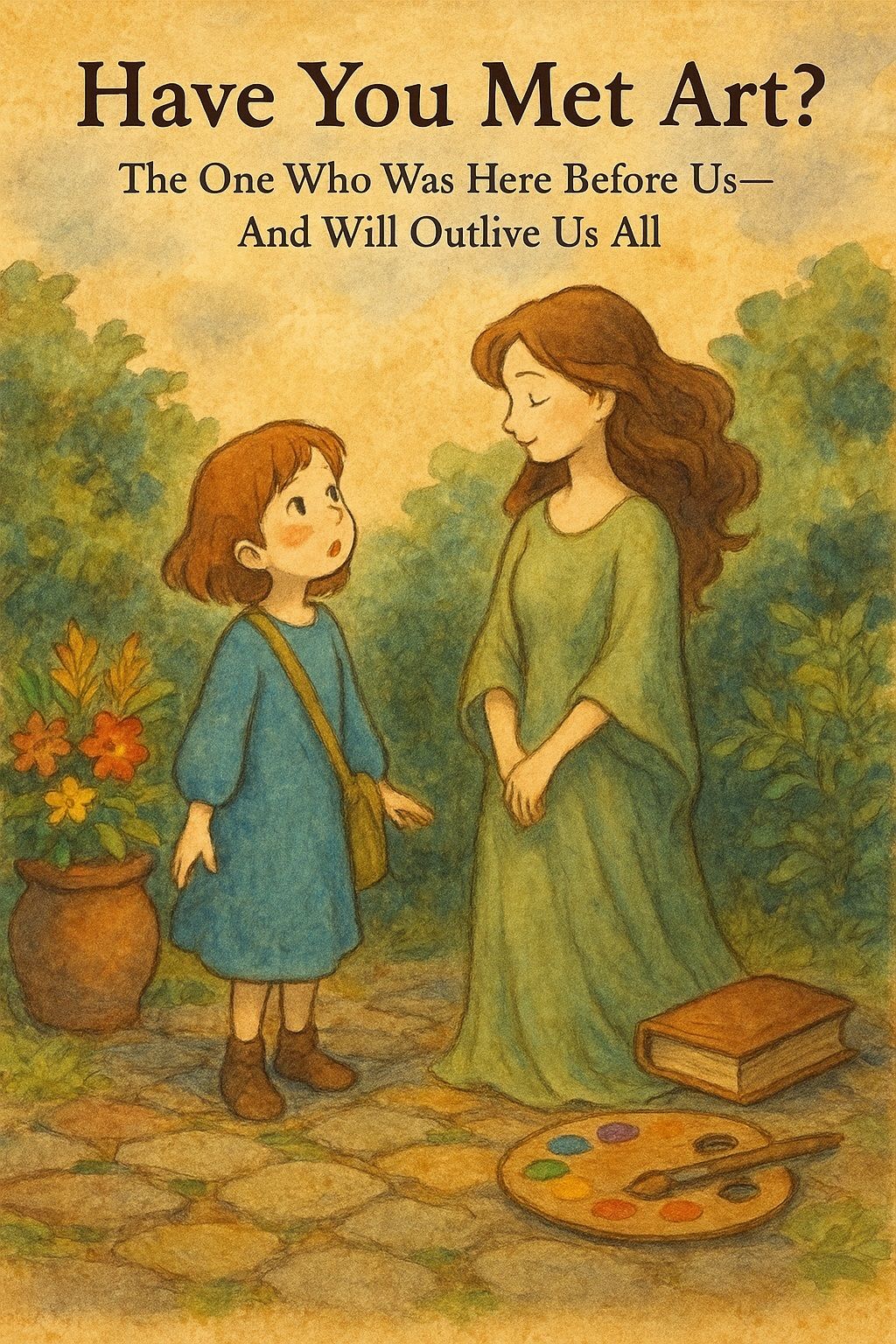

Have You Met Art?

The One Who Was Here Before Us—and Will Outlive Us All

Have you met Art?

She comes in many forms.

She lives in everyone and everything.

You have to know where to look.

Treat her well and she'll turn something you love into something beautiful.

Art's most common forms are music, drawing, and writing.

But she can be found anywhere, even in still waters or heavy thunderstorms.

Sometimes, Art is looked down on.

But she doesn't mind, she knows her value.

Art knows that she is in everyone, and even though some people don’t express her, she makes sure never to leave them.

And for the people who do express her?

Well, she helps them make beautiful things and gives them talent.

More importantly, she was there before us (for those who were before us), and she will be here after us, for the people to come.

Years may pass.

Decades may pass.

Centuries may pass.

But Art will be there to see that the next generation to come knows that she is everywhere and always will be.

The Figures of Speech Hidden in Darimeka’s Have You Met Art?

Darimeka’s piece does something that excellent writing has always done—without even trying to show off. She uses four influential figures of speech that give her words the pulse of poetry and the weight of timelessness.

✅ Personification

What does it mean:

This is when you attribute human qualities to something non-human, so that it appears to breathe, speak, and feel.

How Darimeka uses it:

She turns Art into a living being. Art doesn’t just exist;

“She lives in everyone and everything.”

“She knows her value.”

Art has a personality, a mind, and even emotions. She becomes not just an idea, but a companion. This is what makes the piece feel alive.

✅ Epiphora

What does it mean:

This is the repetition of the same word or phrase at the end of consecutive lines—used to create rhythm, emphasis, and emotional build-up.

How Darimeka uses it:

Her closing lines—

“Years may pass

Decades may pass

Centuries may pass...”

This repetition doesn’t just sound beautiful—it gives the poem a sense of eternity. It makes time itself feel like a character, marching on while Art watches, unchanged.

Anaphora = repetition at the start of lines.

Epiphora = repetition at the end of lines.

✅ Metaphor

What does it mean:

A metaphor is when you describe something by saying it is something else, without using “like” or “as.”

How Darimeka uses it:

The entire poem is built on one great unspoken metaphor:

Art is a living presence.

She never says “Art is like a person”—she writes as if Art is a person. That’s the beauty of metaphor: it’s not a comparison. It’s an invitation to believe.

Together, these four poetic tools give her writing the mythic depth that makes it feel older than time, but fresh in the telling.

✅ Is This an Apostrophe?

Apostrophe

What does it mean:

This is when the writer speaks directly to someone or something that isn’t physically present—a kind of poetic summoning.

How Darimeka uses it:

The very first line—

“Have you met Art?”

She’s not just talking to readers. She’s inviting Art herself into the room, calling her forth like an ancient muse. It’s subtle, but this direct address gives the whole piece its ritualistic, intimate feel.

However…

At first glance, I described this poem as an example of apostrophe—the classical literary device where a writer speaks directly to something absent, abstract, or personified: “O Death,” “O Muse,” “O Wild West Wind.”

But on closer inspection—thanks to not trusting AI—I realized this isn’t quite right.

In Darimeka’s poem, Art is not addressed. Art is introduced: “Have you met Art?”

The speaker is speaking to us, the reader, not to Art. Art is talked about, not spoken to.

This distinction matters. In strict literary terms, this is personification—giving Art a voice, a mind, a presence—but not apostrophe, which would require the speaker to turn and speak directly to Art herself.

And yet—there’s something more subtle at work. By introducing Art, the poem summons her into presence. Art is there, listening, waiting, even if she hasn’t yet been addressed.

In that sense, while not formally apostrophic, the poem carries its energy: the act of calling forth an unseen presence into the reader’s awareness. A soft invocation. An opening of the door.

This is the more profound truth of all introductions: they prepare the field for encounter.